Parkersburg legislative interim meetings begin with review of occupational licensing reform, scope of practice

PARKERSBURG — Lawmakers received a briefing Sunday on opening West Virginia’s occupational licensing regulations to allow workers from other states to more easily work in the state and address shortages in ophthalmologists.

Members of the Joint Standing Committee on Government Organization heard a report at Parkersburg City Hall on the first day of September legislative interim meetings in Parkersburg.

Speaking to the committee was Edward Timmons, the director of the Knee Regulatory Research Center with the John Chambers College of Business and Economics at West Virginia University. The Knee Center conducts research on government regulations, specifically looking at certificate of need for health care access, occupational licensing and scope or practice for certain professionals.

Timmons began with a talk about expanding the scope of practice for optometrists. While optometrists can perform eye examinations, diagnose issues and recommend treatments, ophthalmologists perform major medical and surgical procedures for eyes.

But in recent years, some states have been relaxing rules and regulations related to the kinds of medical services that optometrists are allowed to offer. Timmons said the number of ophthalmologists in West Virginia and across the nation is shrinking, but the number of optometrists remains steady.

“There are many more optometrists in West Virginia than there are ophthalmologists, and much like every other state, the number of ophthalmologists in West Virginia is projected to decline,” Timmons said. “There’s going to be more retirements, and there’s just not as many folks entering the market.”

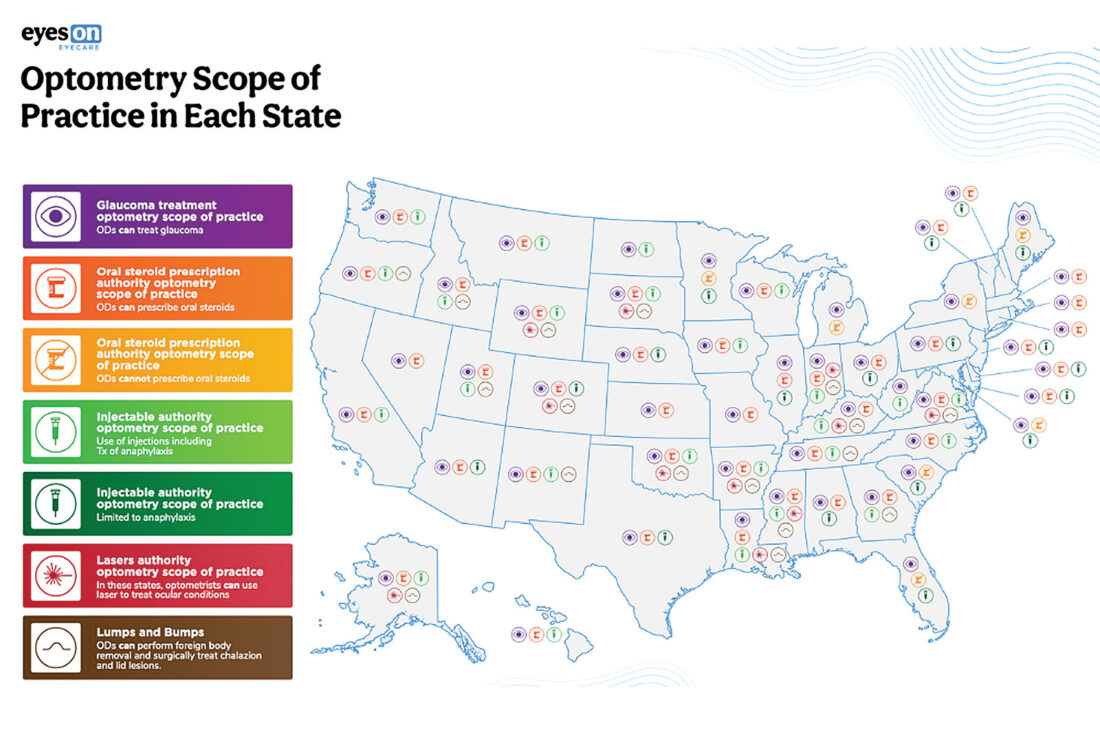

According to Eyes on Eyecare, among services optometrists in West Virginia can offer include some level of oral medication prescription authority, topical treatments for glaucoma, oral steroid treatments and small excision surgery for chalazia/hordeola, etc.

“Historically, we’ve seen a really big shift in what optometrists are able to do and what they’re able to provide to patients,” Timmons said. “If you give patients the opportunity to get treatment from other providers, they’re likely to get that treatment.

In West Virginia, optometrists can use lasers for diagnostics, but not for therapeutic treatment of eye and vision issues. Only 11 states, including neighboring Virginia and Kentucky, allow optometrists to use lasers to treat certain conditions such as post-cataract haze, minor glaucoma treatments and refractive laser surgery, also known as LASIK. Of the 11 states, only Alaska and Oklahoma allow optometrists to perform LASIK surgeries, which are used to treat nearsightedness, astigmatism and other issues.

House Bill 4783 relating to the practice of optometry passed the House of Delegates earlier this year in a 91-2 vote, but the bill never was taken up by the Senate’s Health and Human Resources Committee.

Similar bills have seen fights between the West Virginia Association of Optometric Physicians, which supports the expansion of their scope of practice, and state and national ophthalmologist groups that say allowing expansion of these surgical procedures beyond trained eye surgeons is unsafe.

Timmons cited data from a recent study that looked at the safety record in states and other countries that allow optometrists to perform certain laser procedures and could only find two negative outcomes, though Timmons admitted the study was not comprehensive. Timmons also said optometrists are now being trained in medical schools on how to do common laser procedures, with post-graduate training required in many cases.

“It would seem, based on the evidence we have up to this point, that optometrists are capable of performing this procedure,” Timmons said. “Technology has evolved, I think optometrists have gotten better at performing laser procedures, and everything I’ve read up to this point suggests to me that it would seem the benefits of granting optometrists this authority far outweigh the costs.”

Timmons turned to the issue of occupational licensing reciprocity, also called universal recognition. According to Timmons, West Virginia has the eighth highest fraction of workers who need an occupational license to work in the state. Of all 50 states, West Virginia ranked 33rd for the number of occupations that require a license.

There are 173 licensed occupations in West Virginia, Timmons said. That’s compared to larger states, such as Texas that licenses 199 occupations and Kansas, which licenses 136 occupations.

Timmons said occupational licensing can have benefits, but it also includes costs, such as making it prohibitive for people wanting to start a new business and discourages people from moving from other states with more relaxed occupational licensing requirements.

“You’re reducing supply. You’re making it harder for individuals to begin working, so you’re restricting the number of workers in that particular profession,” Timmons said. “If supply goes down, then we might expect higher prices. Occupational licensing also reduces employment. If you make it harder for individual workers to begin working, fewer workers will be able to take advantage of entering the field and having that opportunity.”

According to Timmons’ research, 26 states offer a form of universal recognition or occupational licensing reciprocity. Some states will accept occupational licenses in good standing. Other states require the license requirements be substantially similar for a license to transfer between states. West Virginia has no laws allowing for universal licensing recognition, while neighboring states Pennsylvania, Ohio and Virginia do.

“Why is it when a barber moves from Pennsylvania to West Virginia they’re not able to practice anymore? That they need to go through a procedure in order to continue working? We have some evidence that this friction is actually dissuading people from moving,” Timmons said. “If a professional is able to provide high-quality service and they have a track record and a reputation, then it’s not necessarily clear those different inputs are making a difference.”

According to Knee Center research, states that implement universal recognition see a 1% bump in the employment ratio due to an increase in new workers and new residents coming to those states to work.

“We find that once this reform gets passed, unemployment comes down for a lot of those licensed workers and labor force participation comes up,” Timmons said. “We think a lot of those folks facing that friction…if they were following their spouse to a new state and their license transfers, then those folks are better able to get into the labor market.”

The House of Delegates passed a bill in 2021 allowing for transfer of out-of-state occupational licensing. House Bill 2007 passed 65-33 in the House and was recommended for passage by the Senate Government Organization Committee, but the bill was never taken up by the Senate Judiciary Committee.