McKinley, Mooney campaign ads stay focused on negative attacks

- The campaigns of Reps. David McKinley and Alex Mooney have flooded the airwaves with negative ads and mailboxes with mailers attacking each other. (Photo by John McCabe)

The campaigns of Reps. David McKinley and Alex Mooney have flooded the airwaves with negative ads and mailboxes with mailers attacking each other. (Photo by John McCabe)

CHARLESTON — With around 10 days until the May 10 primaries in West Virginia, U.S. Reps. David McKinley and Alex Mooney are traversing the new 2nd District and introducing themselves to new voters.

But the first thing most voters will see will be the onslaught of negative TV and radio ads and mailers.

The campaign to win the Republican primary between McKinley, in his sixth term representing the old 1st Congressional District, and Mooney, in his fourth term representing the old 2nd Congressional District, has been ugly ever since the West Virginia Legislature combined parts of their district into the new northern 2nd District.

Mooney started putting TV ads on the air attacking McKinley for being one of 13 Republicans in the House of Representatives to vote for the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in November. The bill also was supported by Sens. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., and Shelley Moore Capito, R-W.Va., but it was opposed by Mooney and 3rd District Rep. Carol Miller, who has a Republican primary of her own in the new southern 1st Congressional District.

“(McKinley) betrayed you,” the announcer on one Mooney ad says. “McKinley backed (President Joe) Bide for a $1 trillion spending spree that’s creating record inflation. David McKinley sold us out.”

Mooney also has attacked McKinley for his vote to create a bipartisan commission to investigate the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol by supporters of former president Donald Trump to stop the certification of the 2020 election for Biden, a former vice president and U.S. senator.

The bill failed, and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi instead created a select committee to investigate Jan. 6, which McKinley opposes.

On the other hand, McKinley has attacked Mooney regarding the ongoing investigation by the House Ethics Committee into Mooney over allegedly improper campaign finance expenses, using congressional and campaign staff for personal errands, and obstruction of the investigations by the Office of Congressional Ethics.

Mooney has maintained his innocence and the House Ethics Committee is expected to release its findings later in May. But in one McKinley campaign ad, it claims Mooney is under “federal investigation” despite the fact it is not clear that there are any federal criminal investigations of Mooney beyond the congressional investigation. The same ad, along with others, also hit Mooney for being a career politician, having been a Maryland lawmaker for many years and a failed congressional candidate in New Hampshire and Maryland. The ad quotes a 2014 article in Forbes magazine “Alex Mooney: the portrait of a political prostitute.”

“Mooney, an opportunistic career politician who has never had a job outside of politics,” the announcer on one ad says. “He’s run for office in three different states. Mooney moved to West Virginia from Maryland so he could get elected to Congress. Now Mooney is under federal investigation for violating the law. Maryland Sen. Alex Mooney: Out for himself, not West Virginia.”

A look at both YouTube accounts for the McKinley and Mooney campaigns show no ads where both candidates introduce themselves to voters, explain their backgrounds and qualifications, and ask for the votes of new constituents in the combined district who have never seen McKinley or Mooney’s name on a ballot. The ads are all attacks on the other candidates.

Scott Widmeyer, the founding managing partner of FINN Partners in Washington, D.C., is the co-founder of the Bonnie and Bill Stubblefield Institute for Civil Political Communications at Shepherd University at Shepherdstown, W.Va. A native of Martinsburg, Widmeyer has been watching the race between McKinley and Mooney with disappointment.

That disappointment led Widmeyer to pen an op-ed for The Journal in March criticizing both McKinley and Mooney for the tone of the race, the negative campaign ads and the lack of any real substantive discussion of issues facing West Virginians in the new district.

More than a month since writing that op-ed, Widmeyer said the vitriol has not improved.

“I don’t think it’s gotten any better,” Widmeyer said by phone Thursday. “I think the voters in this new district are kind of seeing the worst of both candidates in terms of their ability to be civil and to run a campaign that speaks to the issues. I don’t think that we’re seeing that.”

“I sit on the board of the Stubblefield Institute … and our focus is we’re trying to create a new scenario not only in West Virginia but in the country where we get the public to take a much more constructive look at politics and the political system that exists,” Widmeyer said. “If we expect the public to do that, we have to have candidates that wage campaigns that are issue-focused and are based on facts and not the name calling that we’ve seen consistently from Mr. Mooney and Mr. McKinley.”

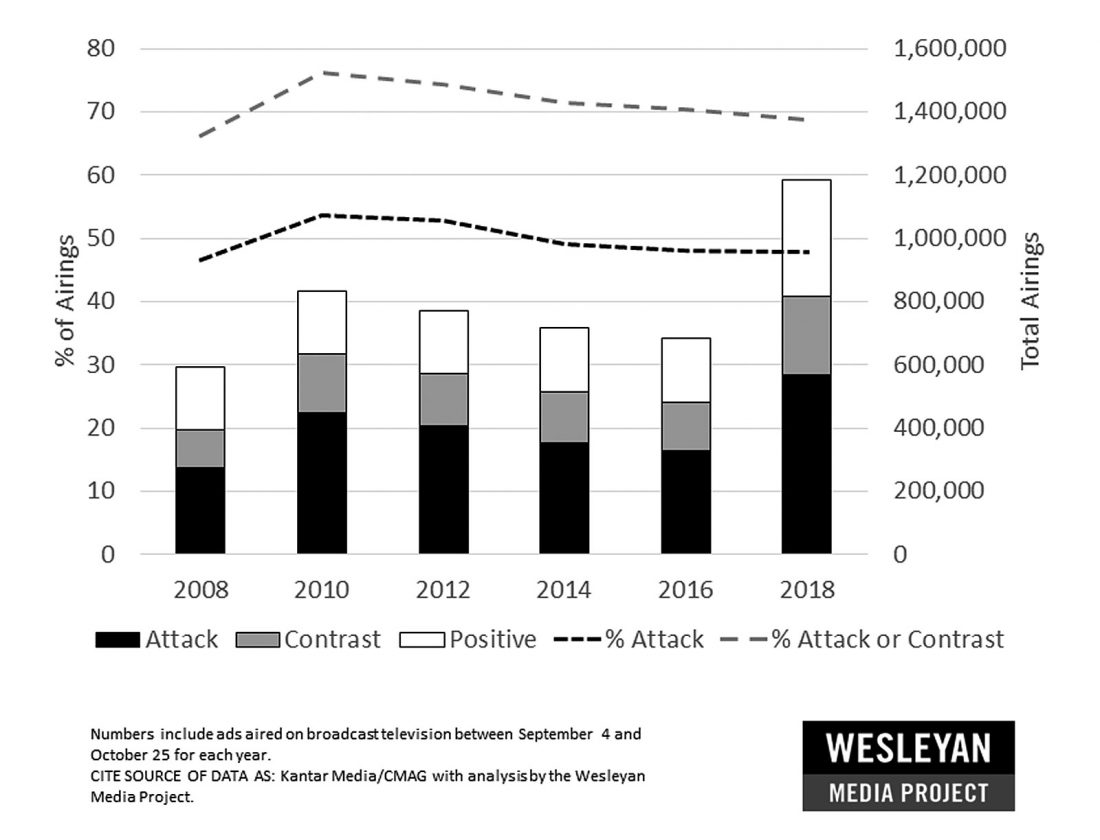

The McKinley and Mooney campaigns are not outliers. Political campaigns, particularly at the congressional level, have gotten more negative over the last several midterm election cycles that fall between presidential elections. According to the Wesleyan Media Project which tracks political advertising, the volume of ads between the 2010 and 2018 for federal races increased, with the vast majority of ads being attack ads.

Wesleyan Media Project data shows that more than 450,000 campaign ad airings in 2010 were attack ads versus approximately 569,000 attack ad airings in 2018.

Alison Ledgerwood, a professor of psychology at the University of California-Davis, studies the effects of positive and negative messaging. In a 2013 paper with Amber Boydstun, a Political Science professor at UC-Davis, Ledgerwood and Boydstun said negative messages stick in the brain better than positive ones. This holds true to negative campaign ads. They said a negative message, or “loss frame,” hangs out in the brain longer than a positive message, or “gain frame,” with it being harder to counter a negative message with a positive message.

“We propose that loss frames are stickier than gain frames in their ability to shape people’s thinking,” they wrote. “Specifically, we suggest that the effect of a loss frame may linger longer than that of a gain frame in the face of reframing and that this asymmetry may arise because it is more difficult to convert a loss-framed concept into a gain-framed concept than vice versa.”

A 2021 study by researchers at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University found the tone of an ad makes a huge difference in driving turnout. The researchers found if only positive ads were run in the 2000 presidential race between George W. Bush and Al Gore, overall voter turnout would have increased by 50.4 percent, while only airing negative ads would have decreased voter turnout by 48.8 percent.

“Positive ads have a much larger and significant turnout stimulation effect,” said Brett Gordon, a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School, for the school’s “Kellogg Insight” publication. “We as citizens should be concerned about the motivation for candidates to rely on negative ads and be aware this is an influence on our political life.”

“I don’t think the public in general likes the idea of these attack ads,” Widmeyer said. “It gets old, and it definitely depresses turnout. In these midterm elections, you’re, you’re probably lucky if you get 30 percent turnout.”

Widmeyer said the Stubblefield Institute tried inviting both McKinley and Mooney to participate in a town hall-style debate, but only McKinley agreed. Instead, the institute invited both McKinley and Mooney to participate in separate town hall events. Mooney declined, citing a scheduling conflict which turned out to be a tele-town hall.

McKinley accepted the invite for the town hall, which took place Monday evening.

“We tried desperately to get both of these candidates to come to Shepherd to do a town hall sort of debate. Congressman McKinley did agree to a debate. Mr. Mooney never agreed to it,” Widmeyer said.

Widmeyer said both McKinley and Mooney are likely showing voters a better side of themselves at campaign events, visits with local officials, and while in the view of the public. But for many voters, the first and only thing they might see of the candidates are the ads they see and hear and the mailers they receive, leaving an entirely different impression.

“The advertising probably has the biggest impact because that’s where you have the larger audience,” Widmeyer said. “For example, when McKinley showed up at Shepherd the other day, he was very civil in terms of how he presented himself, but we had 65 to people in the audience and probably another couple hundred at the most online, which doesn’t, which pales in comparison to the number of people who might be seeing the attack ads.”

Despite the attacks, Widmeyer said most voters would be surprised to know there is little daylight between McKinley and Mooney. Both have conservative voting records. Both actively supported Trump and his agenda when president (McKinley actually has a better record at voting for Trump’s agenda than Mooney). And both are solid on traditional Republican issues, such as 2nd Amendment rights, anti-abortion and pro-fossil fuels.

“At the end of the day, you have to look at both of them and say they’re both pretty much Trump loyalists,” Winmeyer said. “They both heavily supported Trump policy, so very little difference in the two when it comes to that.”

“We want to get to a better place in this country with our political system, and we have a long way to go,” Widmeyer continued. “There are a lot of reasons that this has built up over the years and it’s even more disconcerting in West Virginia right now because the state is going through a loss of population, and we’ve lost a congressional seat. And now we see two sitting members of Congress going after each other and they’re not from different parties; they’re from the same party. We don’t believe that is useful.”

Steven Allen Adams can be reached at sadams@newsandsentinel.com.